Classical Chinese studies in 20th century Vietnam and future implications

photo courtesy of Trần Quang Đức

A large inspiration for the creation of this blog was the blog Kuiwon (歸源 , Quy Nguyên) which showcases works written in Classical Chinese by Korean authors from various periods of Korean history. After following this blog for a period of time, I consulted with its author who then encouraged me to do something similar with Classical Chinese works written by Vietnamese authors. As I mentioned in an interview with Người Việt Daily News (日報𠊛越 , Nhật Báo Người Việt) several months ago, it is impossible to have a profound understanding of Vietnamese culture and people without at least rudimentary knowledge of Classical Chinese studies (漢學 , Hán học). This is evident from the fact that a huge number of Vietnamese people, both in Vietnam and abroad, are in a state of total disconnect with their people’s past cultural and historical heritage. I have met a number of Vietnamese people to whom I have had difficulty explaining that modern written Vietnamese is simply a romanization of chữ Nôm (字喃), an older writing system based on Chinese characters. Similarly, many of my Vietnamese acquaintances express confusion when I explain that Vietnamese family names are also shared by Chinese and Korean people, or that most given names are sino-Vietnamese (漢越 , Hán-Việt) and therefore can be written with Chinese characters. It would be reassuring if my experience was not representative of a majority, however, my interactions with people living both in Vietnam and abroad have confirmed this widespread ignorance. This ignorance of Vietnamese history and culture seeps into almost every conceivable area. For example, many people assume that the áo dài (襖𨱽) is representative of traditional “pure Vietnamese” (純越 , thuần Việt) clothing. In reality, precursors to the modern áo dài were only widely adopted (by force) during the 19th century under the rule of Nguyễn Thánh Tổ (阮聖祖 , 1791-1841). The áo dài in its modern form, like the one I am wearing in the picture below, was most likely not finalized until the early 1900s, and even then was only one of many different robes worn by Vietnamese people. Like most things, especially clothing, it did not develop in isolation, but had similar counterparts in Ch’ing dynasty China.

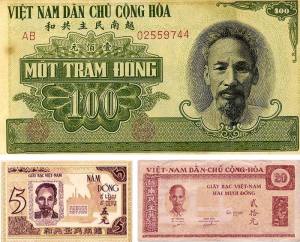

In fact, the disastrous results of abandoning Classical Chinese studies were already foreseen by Vietnamese intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century. Scholars such as Phạm Quỳnh (範瓊 , 1892-1945) who were well-versed in both Western and Classical Chinese studies saw clearly that ,although Western studies had to be adopted in order to advance the country, Classical Chinese studies were still essential to Vietnamese culture and the future of Vietnam. Before and during the period Vietnam was divided between North and South (1954-1975), Chinese characters were still used on money, on advertisements in the marketplace, birth records, and could be seen around in various locations, as shown by the photo at the top of this post which shows Chinese characters in private homes, school classrooms, and libraries. Classical Chinese was also taught as a foreign language in the universities of South Vietnam. The position of the Communist North, which eventually conquered all of Vietnam, towards Classical Chinese has been mixed. The Communists, relying on the support of uneducated peasants and commoners as they did, in the past have been violently opposed to Classical Chinese, which they saw as foreign influence or something belonging to the upper class. Attempts to purge the Vietnamese language of Classical Chinese vocabulary in order to create a “pure Vietnamese” (純越 , thuần Việt) language had comical results that have since been abandoned in part. Today, this anti-Chinese vocabulary stance has been reversed and people in Vietnam use a great deal of sino-Vietnamese vocabulary, often incorrectly, as discussed in this brief television interview.

photo courtesy of Trần Quang Đức

I mentioned in my newspaper interview that culture is not something to be merely “preserved” (保存 , bảo tồn) , but that it must be “developed” (發展 , phát triển) as well. Earlier this year, I had an opportunity to meet and speak with Emmy award winning musician Võ Vân Ánh (武雲映). In our conversation, she mentioned that, in studying traditional Vietnamese instruments and music, her goal is never to simply preserve traditional music, but rather to use traditional music as a foundation on which she can make creative contributions to Vietnamese musical culture. One criticism that I have often faced is that many people claim Classical Chinese studies to be a useless remnant of the past, irrelevant to the modern world. Today more than ever, Vietnamese people in Vietnam and abroad face many threats to their country and culture. If Vietnamese culture is to survive, the Vietnamese people must first have a firm understanding of what exactly it means to be Vietnamese in a rapidly changing modern world. This is impossible without a foundation in Classical Chinese studies and Vietnamese history. In promoting Classical Chinese studies, my goal is never simply a vain dream to return to an imagined “golden-age” from the distant past. If Vietnam is ever going stand level with countries like Japan and South Korea, the Vietnamese people must first learn to embrace and develop aspects of culture including those that received heavy Chinese influence. To be in constant denial and shame of Chinese elements in Vietnamese culture is childish and produces nothing but crackpot scholarship and a collective inferiority complex that leads to the Vietnamese youth, especially those born overseas, looking to other countries for authentic “Asian” culture.

As such, I will be taking a hiatus from translating poetry in order to translate prose written during the 20th century regarding the role of Classical Chinese studies in Vietnamese culture and literature. These works will be translated mainly from Vietnamese sources coming from major authors such as Phạm Quỳnh (範瓊 , 1892-1945) and Nguyễn Khắc Hiếu (阮克孝 , 1889-1939). These translations will serve a two-fold purpose. First, the selected works will show just how saturated Vietnamese culture really was with Classical Chinese learning. This is shown through the beautifully written prose, which often employs are large percentage of sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and references to Classical Chinese literature, and the arguments which the authors put forth. Secondly, I hope that by translating these works into English and also posting the original Vietnamese text (some of which is not necessarily easily accessible in most library systems), modern readers will be able to see that supporters of “old learning” (舊學 , cựu học) were actually very forward thinking intellectuals with concern for the country at heart, not a bunch of crusty Confucians prudes as they are often depicted as being. To Vietnamese readers of this blog: I hope that those who are not yet fluent in the Vietnamese language will be inspired to study our language and culture, to those who are already fluent in Vietnamese, I hope that you will undertake study of Classical Chinese or at least a deeper critical study of Vietnam’s history and culture. What our forefathers envisioned in the early 20th century was a future Vietnam that could keep pace with the West and at the same time preserve our distinctly Oriental culture. Today, the ease with which one can access learning resources has finally brought the ideal of a Vietnamese intellectual well-versed both in the ways of the West and the East within the reach of an overwhelming number of Vietnamese people. At this crucial juncture of Vietnamese history, I can only hope to lend a hand in what I dream will eventually be a resurgence of Classical Chinese learning and Vietnamese culture.

History is what it is. To deny China’s influence in Vietnamese culture and literature is to blithely ignore the thousands of years of history between these two neighbors and to engage in revisionist history. That being said, it does not imply that Vietnam does not have its own identity, its own unique literary tradition. Rather, it points to the strength of the people that have resisted assimilation, culturally and linguistically, from repeated invasion attempts by China. The use of the Chinese characters and later, Vietnamese chữ Nôm, represents the norm at the time and does not mean acquiescence. As you pointed out, the Chinese’s Hán was the shared literary language in that region (also used in Korea and Japan) during those periods.

I agree with your assertion of the need to understand the past in order to have a deeper understanding of one’s heritage; in Vietnam’s case, it’s to improve appreciation for the rich literary tradition made possible through study of the classics. I also agree with you that without that important understanding, today’s younger generations of Vietnamese cannot fully appreciate the richness of their culture heritage. I applaud your effort in this important endeavor and hope that the critics will recognize that through this effort, you’re not being Sino-centrist, but rather, you’re showing yourself as a true patriot. Best of luck.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you think its possible to create a script in a manner similar to hangul that could represent all the morphemes of a tonal language with diverse phonology such as Vietnamese as a single block morpheme with tones? Would this allow for a mixed script to be used for Vietnamese allowing Vietnamese to write with chữ Hán side by side without being an orthographic nightmare while making it easier to deduce the sound represented by chữ nôm in historical texts?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s an interesting thought. I vaguely remember reading some where that the 19th century Catholic reformer Nguyen Truong To proposed creating a new writing system based off of Japanese instead of the Quoc Ngu romanization. I haven’t been able to locate the source, and this information may be spurious. The creation of the a new script at this point in history would be difficult…the Quoc Ngu romanization already boasts a huge corpus of valuable literature and cultural contributions.

LikeLike

It would be cool if we create a new writing systems based on Chu han, however it will be a major inconvenience for using technology. Then we will have to install new keyboards not to mention replace all official signs and rewrite official documents. It will be such a hassle but I think in the future when Vietnam becomes a richer country we should do this. The Latin alphabet has no connection to our culture, it’s artificial and meaningless. I cringe when I see New Years couplets written in latin characters as well as temples being built with latin characters instead of Chu han

LikeLike